- Invasion Of The Squares From The Fifth Dimension Mac Os X

- Invasion Of The Squares From The Fifth Dimension Mac Os 7

- Invasion Of The Squares From The Fifth Dimension Mac Os Catalina

- Invasion Of The Squares From The Fifth Dimension Mac Os Download

A five-dimensional space is a space with five dimensions. In mathematics, a sequence of Nnumbers can represent a location in an N-dimensionalspace. If interpreted physically, that is one more than the usual three spatial dimensions and the fourth dimension of time used in relativistic physics.[1] Whether or not the universe is five-dimensional is a topic of debate.[citation needed]

Physics[edit]

Blood of the Cybermen was the second episode of the video game Doctor Who: The Adventure Games.The player had the ability to play as the Eleventh Doctor and Amy Pond.Though the Cybermen in this game resembled those from a parallel universe, they also had a different logo on their chests.

Much of the early work on five-dimensional space was in an attempt to develop a theory that unifies the four fundamental interactions in nature: strong and weak nuclear forces, gravity and electromagnetism. German mathematician Theodor Kaluza and Swedish physicist Oskar Klein independently developed the Kaluza–Klein theory in 1921, which used the fifth dimension to unify gravity with electromagnetic force. Although their approaches were later found to be at least partially inaccurate, the concept provided a basis for further research over the past century.[1]

To explain why this dimension would not be directly observable, Klein suggested that the fifth dimension would be rolled up into a tiny, compact loop on the order of 10-33 centimeters.[1] Under his reasoning, he envisioned light as a disturbance caused by rippling in the higher dimension just beyond human perception, similar to how fish in a pond can only see shadows of ripples across the surface of the water caused by raindrops.[2] While not detectable, it would indirectly imply a connection between seemingly unrelated forces. The Kaluza–Klein theory experienced a revival in the 1970s due to the emergence of superstring theory and supergravity: the concept that reality is composed of vibrating strands of energy, a postulate only mathematically viable in ten dimensions or more. Superstring theory then evolved into a more generalized approach known as M-theory. M-theory suggested a potentially observable extra dimension in addition to the ten essential dimensions which would allow for the existence of superstrings. The other 10 dimensions are compacted, or 'rolled up', to a size below the subatomic level.[1][2] The Kaluza–Klein theory today is seen as essentially a gauge theory, with the gauge being the circle group.[citation needed]

The fifth dimension is difficult to directly observe, though the Large Hadron Collider provides an opportunity to record indirect evidence of its existence.[1] Physicists theorize that collisions of subatomic particles in turn produce new particles as a result of the collision, including a graviton that escapes from the fourth dimension, or brane, leaking off into a five-dimensional bulk.[3] M-theory would explain the weakness of gravity relative to the other fundamental forces of nature, as can be seen, for example, when using a magnet to lift a pin off a table — the magnet is able to overcome the gravitational pull of the entire earth with ease.[1]

Mathematical approaches were developed in the early 20th century that viewed the fifth dimension as a theoretical construct. These theories make reference to Hilbert space, a concept that postulates an infinite number of mathematical dimensions to allow for a limitless number of quantum states. Einstein, Bergmann and Bargmann later tried to extend the four-dimensional spacetime of general relativity into an extra physical dimension to incorporate electromagnetism, though they were unsuccessful.[1] In their 1938 paper, Einstein and Bergmann were among the first to introduce the modern viewpoint that a four-dimensional theory, which coincides with Einstein-Maxwell theory at long distances, is derived from a five-dimensional theory with complete symmetry in all five dimensions. They suggested that electromagnetism resulted from a gravitational field that is “polarized” in the fifth dimension.[4]

The main novelty of Einstein and Bergmann was to seriously consider the fifth dimension as a physical entity, rather than an excuse to combine the metric tensor and electromagnetic potential. But they then reneged, modifying the theory to break its five-dimensional symmetry. Their reasoning, as suggested by Edward Witten, was that the more symmetric version of the theory predicted the existence of a new long range field, one that was both massless and scalar, which would have required a fundamental modification to Einstein's theory of general relativity.[5]Minkowski space and Maxwell's equations in vacuum can be embedded in a five-dimensional Riemann curvature tensor.[citation needed]

In 1993, the physicist Gerard 't Hooft put forward the holographic principle, which explains that the information about an extra dimension is visible as a curvature in a spacetime with one fewer dimension. For example, holograms are three-dimensional pictures placed on a two-dimensional surface, which gives the image a curvature when the observer moves. Similarly, in general relativity, the fourth dimension is manifested in observable three dimensions as the curvature path of a moving infinitesimal (test) particle. 'T Hooft has speculated that the fifth dimension is really the spacetime fabric.[citation needed]

- The 5th Dimension is an American popular music vocal group, whose repertoire includes pop, R&B, soul, jazz, light opera and Broadway – a melange referred to as 'champagne soul'. Formed as the Versatiles in late 1965, the group changed its name to 'the 5th Dimension' by 1966. Between 1967 and 1973 they charted with 19 Top 40 hits on Billboard ' s Hot 100, two of which – 'Up – Up and Away.

- Will operating system updates for the iPad be free like the iPhone or will they cost money like the iPod touch? As first spotted by MacRumors in the original iPad licensing agreement, the next major version of the operating system (4.x) would be provided free of charge. Indeed, iOS 4 was provided free of charge.

- At PowerMax, we sell new and used Macs. Our used Macs often come with previous versions of Mac OS X, and our customers sometimes would like to know what the differences are between different versions. The following article is a synopsis of each major OS X version since OS X 10.4 Tiger.

Five-dimensional geometry[edit]

According to Klein's definition, 'a geometry is the study of the invariant properties of a spacetime, under transformations within itself.' Therefore, the geometry of the 5th dimension studies the invariant properties of such space-time, as we move within it, expressed in formal equations.[6]

Polytopes[edit]

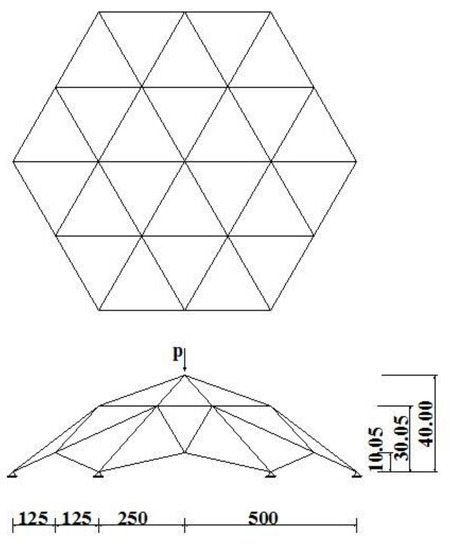

In five or more dimensions, only three regular polytopes exist. In five dimensions, they are:

- The 5-simplex of the simplex family, {3,3,3,3}, with 6 vertices, 15 edges, 20 faces (each an equilateral triangle), 15 cells (each a regular tetrahedron), and 6 hypercells (each a 5-cell).

- The 5-cube of the hypercube family, {4,3,3,3}, with 32 vertices, 80 edges, 80 faces (each a square), 40 cells (each a cube), and 10 hypercells (each a tesseract).

- The 5-orthoplex of the cross polytope family, {3,3,3,4}, with 10 vertices, 40 edges, 80 faces (each a triangle), 80 cells (each a tetrahedron), and 32 hypercells (each a 5-cell).

An important uniform 5-polytope is the 5-demicube, h{4,3,3,3} has half the vertices of the 5-cube (16), bounded by alternating 5-cell and 16-cell hypercells. The expanded or stericated 5-simplex is the vertex figure of the A5 lattice, . It and has a doubled symmetry from its symmetric Coxeter diagram. The kissing number of the lattice, 30, is represented in its vertices.[7] The rectified 5-orthoplex is the vertex figure of the D5 lattice, . Its 40 vertices represent the kissing number of the lattice and the highest for dimension 5.[8]

| A5 | Aut(A5) | B5 | D5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5-simplex {3,3,3,3} | Stericated 5-simplex | 5-cube {4,3,3,3} | 5-orthoplex {3,3,3,4} | Rectified 5-orthoplex r{3,3,3,4} | 5-demicube h{4,3,3,3} |

Hypersphere[edit]

A hypersphere in 5-space (also called a 4-sphere due to its surface being 4-dimensional) consists of the set of all points in 5-space at a fixed distance r from a central point P. The hypervolume enclosed by this hypersurface is:

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ abcdefgPaul Halpern (April 3, 2014). 'How Many Dimensions Does the Universe Really Have'. Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ^ abOulette, Jennifer (March 6, 2011). 'Black Holes on a String in the Fifth Dimension'. Discovery News. Archived from the original on November 1, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ^Boyle, Alan (June 6, 2006). 'Physicists probe fifth dimension'. NBC news. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ^Einstein, Albert; Bergmann, Peter (1938). 'On A Generalization Of Kaluza's Theory Of Electricity'. Annals of Mathematics. 39 (3): 683–701. doi:10.2307/1968642. JSTOR1968642.

- ^Witten, Edward (January 31, 2014). 'A Note On Einstein, Bergmann, and the Fifth Dimension'. arXiv:1401.8048 [physics.hist-ph].

- ^Sancho, Luis (October 4, 2011). Absolute Relativity: The 5th dimension (abridged). p. 442.

- ^http://www.math.rwth-aachen.de/~Gabriele.Nebe/LATTICES/A5.html

- ^Sphere packings, lattices, and groups, by John Horton Conway, Neil James Alexander Sloane, Eiichi Bannai[1]

Invasion Of The Squares From The Fifth Dimension Mac Os X

Further reading[edit]

- Wesson, Paul S. (1999). Space-Time-Matter, Modern Kaluza-Klein Theory. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN981-02-3588-7.

- Wesson, Paul S. (2006). Five-Dimensional Physics: Classical and Quantum Consequences of Kaluza-Klein Cosmology. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN981-256-661-9.

- Weyl, Hermann, Raum, Zeit, Materie, 1918. 5 edns. to 1922 ed. with notes by Jūrgen Ehlers, 1980. trans. 4th edn. Henry Brose, 1922 Space Time Matter, Methuen, rept. 1952 Dover. ISBN0-486-60267-2.

External links[edit]

Apple’s latest updates to both iOS and OS X have largely banished skeuomorphism—design elements that imitate real-world counterparts. (The leather textures in Mountain Lion’s Calendar, Contacts, and Notes applications are the most familiar examples.) Much like iOS 7, OS X Mavericks strips out those gaudier elements of Apple’s past designs and flattens faux-3D textures. Here are some of the visual changes you will likely notice in the new Mac OS.

Leather be gone

According to legend, Steve Jobs so admired the leather texture of the seats in his private jet that he demanded Apple’s designers incorporate such a texture into the Calendar, Contacts, and Notes applications (complete with stitching). As much as we love Jobs’s vision for most things, though, his obsession with rich Corinthian leather is one we’re happy to see fade away in OS X Mavericks.

Not only has the leather border disappeared from each of the above-mentioned programs, but you’ll also no longer find faux binding stitches holding your address book together in Contacts. Without all the skeuomorphic elements, the application now has room for a title bar, which displays the number of contacts within the selected group. And Notes loses its torn-paper border at the top of each note as well as the small hieroglyphics-like trash icon at the bottom of each note—because presumably we all understand the function of the Mac’s Delete key.

Invasion Of The Squares From The Fifth Dimension Mac Os 7

Clean linen

Though the Corinthian leather was perhaps the most prominent texture in Lion and Mountain Lion, another was lurking about: dark linen.

Invasion Of The Squares From The Fifth Dimension Mac Os Catalina

That subtle pattern of white and gray threads appeared in the background of Notification Center, Mission Control, and even OS X’s Accounts window. But no more: It too has been given the heave-ho. Where once you saw linen, now you have dark gray.

Invasion Of The Squares From The Fifth Dimension Mac Os Download

Not content to strip out merely the leather and linen, Apple’s designers also went after some less noticeable textures. If you compare Mavericks’s DVD Player to the one found in Mountain Lion, for instance, you’ll find that controls such as Video Zoom, Video Color, and Audio Equalizer are less transparent than their Mountain Lion counterparts. The Dashboard background was once littered with Lego-like dots; it’s now a smooth gray grid. And certain icons in System Preferences are flatter, losing their metal texture of old.

Not dead yet

While Apple has made some substantial moves away from skeuomorphic design in Mavericks, it hasn’t banished the look entirely. Visit the Applications folder, and you’ll still find application icons that parrot their purpose: A tabbed address book still represents Contacts, Image Capture sports a point-and-shoot camera, Reminders still resembles a checklist, and TextEdit hasn’t lost its pen or its inspirational (and marketable) words from John Appleseed.

More-blatant examples also remain. Launch Game Center, and—whoa!—the polished wood and green felt textures are still prominently on view. And if you’re interested in how our ancestors in the early 2000s rendered wood, grass, marble, metal, and fur (complete with reflections, in most cases), you need only launch the venerable Chess application.